固定(Pinning)

为了轮询 future,future 首先要用特殊类型 Pin<T> 来固定。如果你读了前面 执行 Future 与任务 小节中关于 Future trait 的解释,你会从 Future::poll 方法的定义中认出 Pin。但这意味什么?我们为什么需要它?

为什么需要固定

Pin 和 Unpin 标记 trait 搭配使用。固定保证了实现了 !Unpin trait 的对象不会被移动。为了理解这为什么必须,我们回忆一下 async/.await 怎么工作吧。考虑以下代码:

let fut_one = ...;

let fut_two = ...;

async move {

fut_one.await;

fut_two.await;

}

这段代码实际上创建了一个实现了 Future trait 的匿名类型,提供了 poll 方法,如下:

// The `Future` type generated by our `async { ... }` block

struct AsyncFuture {

fut_one: FutOne,

fut_two: FutTwo,

state: State,

}

// List of states our `async` block can be in

enum State {

AwaitingFutOne,

AwaitingFutTwo,

Done,

}

impl Future for AsyncFuture {

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<()> {

loop {

match self.state {

State::AwaitingFutOne => match self.fut_one.poll(..) {

Poll::Ready(()) => self.state = State::AwaitingFutTwo,

Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending,

}

State::AwaitingFutTwo => match self.fut_two.poll(..) {

Poll::Ready(()) => self.state = State::Done,

Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending,

}

State::Done => return Poll::Ready(()),

}

}

}

}

当 poll 第一次调用时,它会轮询 fut_one。如果 fut_one 不能完成,那么 AsyncFuture::poll 就会返回。调用 poll 的 Future 会从上次中断的地方继续。这个过程会持续到 future 成功完成。

然而,如果我们在 async 块中用了引用呢?例如:

async {

let mut x = [0; 128];

let read_into_buf_fut = read_into_buf(&mut x);

read_into_buf_fut.await;

println!("{:?}", x);

}

这会编译成什么结构呢?

struct ReadIntoBuf<'a> {

buf: &'a mut [u8], // points to `x` below

}

struct AsyncFuture {

x: [u8; 128],

read_into_buf_fut: ReadIntoBuf<'what_lifetime?>,

}

这里,ReadIntoBuf future 持有了一个指向其他字段 x 的引用。然而,如果 AsyncFuture 被移动了,x 的位置(location)也会被移走,使得存储在 read_into_buf_fut.buf 的指针失效。

固定 future 到内存特定位置则阻止了这种问题,让创建指向 async 块的引用变得安全。

固定的细节

我们来用一个简单点的例子来理解固定吧。我们遇到了上面的问题,这本质是关于我们如何在 Rust 里处理引用和自引用类型(self-referential types)。

我们来看个例子:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Self { Test { a: String::from(txt), b: std::ptr::null(), } } fn init(&mut self) { let self_ref: *const String = &self.a; self.b = self_ref; } fn a(&self) -> &str { &self.a } fn b(&self) -> &String { assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first"); unsafe { &*(self.b) } } } }

Test 类型提供了方法,来获取字段 a 或 b 的引用。因为 b 是指向 a 的引用,但由于 Rust 的借用规则,我们不能定义它的生命周期(lifetime),所以我们把它存成指针。现在我们有了一个自引用结构体了。

如果不把我们的数据四处转移,我们的例子可以运行得很好:

fn main() { let mut test1 = Test::new("test1"); test1.init(); let mut test2 = Test::new("test2"); test2.init(); println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b()); println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b()); } #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Self { Test { a: String::from(txt), b: std::ptr::null(), } } // We need an `init` method to actually set our self-reference fn init(&mut self) { let self_ref: *const String = &self.a; self.b = self_ref; } fn a(&self) -> &str { &self.a } fn b(&self) -> &String { assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first"); unsafe { &*(self.b) } } }

我们可以得到预期结果:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { a: test1, b: test1 a: test2, b: test2 }

来看看如果我们把 test1 和 test2 交换了,会发生什么:

fn main() { let mut test1 = Test::new("test1"); test1.init(); let mut test2 = Test::new("test2"); test2.init(); println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b()); std::mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2); println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b()); } #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Self { Test { a: String::from(txt), b: std::ptr::null(), } } fn init(&mut self) { let self_ref: *const String = &self.a; self.b = self_ref; } fn a(&self) -> &str { &self.a } fn b(&self) -> &String { assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first"); unsafe { &*(self.b) } } }

我们可能以为它只会把 test1 打印了两次:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { a: test1, b: test1 a: test1, b: test1 }

但实际上我们得到得结果是:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { a: test1, b: test1 a: test1, b: test2 }

现在指针 test2.b 仍然指向 test1 内部的旧位置。这个结构体不再是自引用的了,它持有一个指向不同对象的字段的指针。这意味着我们不能依赖 test2.b 的生命周期会和 test2 的生命周期绑定。

如你仍然有些疑惑,以下这个例子应该可以使你信服:

fn main() { let mut test1 = Test::new("test1"); test1.init(); let mut test2 = Test::new("test2"); test2.init(); println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b()); std::mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2); test1.a = "I've totally changed now!".to_string(); println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b()); } #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Self { Test { a: String::from(txt), b: std::ptr::null(), } } fn init(&mut self) { let self_ref: *const String = &self.a; self.b = self_ref; } fn a(&self) -> &str { &self.a } fn b(&self) -> &String { assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first"); unsafe { &*(self.b) } } }

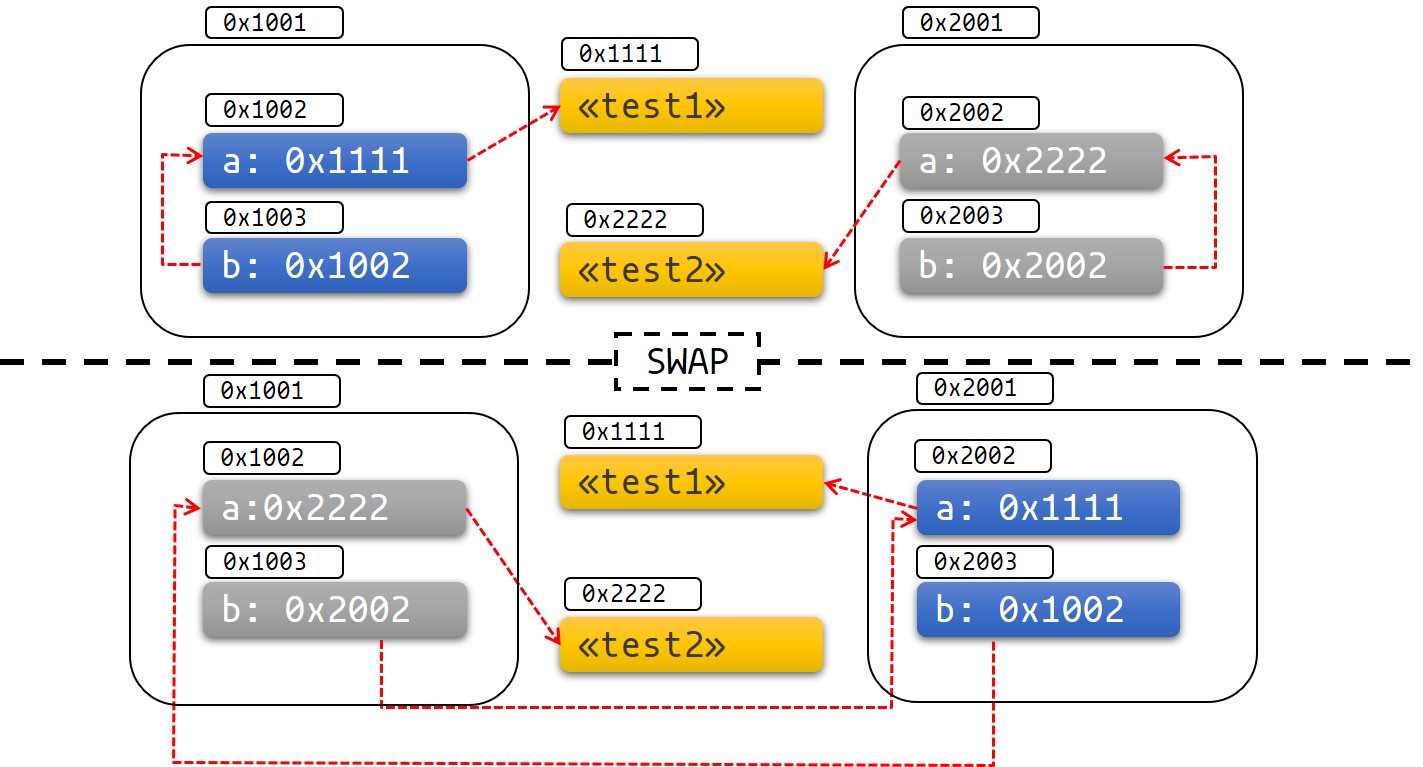

这张图能帮助我们可视化到底发生了什么:

图1:结构体交换前后

这图很容易展现未定义行为(Undefined Behavior, UB)以及其他类似的使用方式可能会出错。

固定的实践

我们来看看固定和 Pin 类型如何帮助我们解决这个问题。

Pin 类型包装了指针类型, 保证没有实现 Unpin 指针指向的值不会被移动。例如, Pin<&mut T>, Pin<&T>, Pin<Box<T>> 都保证了 T 不会被移动,即使 T: !Unpin.

多数类型被移走也不会有问题。这些类型实现了 Unpin trait。指向 Unpin 类型的指针能够自由地放进 Pin,或取走。例如,u8 是 Unpin 的,所以 Pin<&mut T> 的行为就像普通的 &mut T,就像普通的 &mut u8。

然而,那些被固定后不能再移动的类型有一个标记 trait !Unpin。 async/await 创建的 Future 就是一个例子。

固定到栈上

回到我们的例子。我们能用 Pin 来解决我们的问题。我们来看看,如果我们需要用一个固定的指针,我们的例子会编程什么样:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::pin::Pin; use std::marker::PhantomPinned; #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, _marker: PhantomPinned, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Self { Test { a: String::from(txt), b: std::ptr::null(), _marker: PhantomPinned, // This makes our type `!Unpin` } } fn init(self: Pin<&mut Self>) { let self_ptr: *const String = &self.a; let this = unsafe { self.get_unchecked_mut() }; this.b = self_ptr; } fn a(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &str { &self.get_ref().a } fn b(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &String { assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first"); unsafe { &*(self.b) } } } }

如果我们的类型实现了 !Unpin,那么固定这个类型的对象到栈上总是 unsafe 的行为。你可以用像是 pin_utils 的库来在将数据固定到栈上的时候避免写 unsafe。

下面,我们将对象 test1 和 test2 固定到栈上:

pub fn main() { // test1 is safe to move before we initialize it let mut test1 = Test::new("test1"); // Notice how we shadow `test1` to prevent it from being accessed again let mut test1 = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test1) }; Test::init(test1.as_mut()); let mut test2 = Test::new("test2"); let mut test2 = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test2) }; Test::init(test2.as_mut()); println!("a: {}, b: {}", Test::a(test1.as_ref()), Test::b(test1.as_ref())); println!("a: {}, b: {}", Test::a(test2.as_ref()), Test::b(test2.as_ref())); } use std::pin::Pin; use std::marker::PhantomPinned; #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, _marker: PhantomPinned, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Self { Test { a: String::from(txt), b: std::ptr::null(), // This makes our type `!Unpin` _marker: PhantomPinned, } } fn init(self: Pin<&mut Self>) { let self_ptr: *const String = &self.a; let this = unsafe { self.get_unchecked_mut() }; this.b = self_ptr; } fn a(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &str { &self.get_ref().a } fn b(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &String { assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first"); unsafe { &*(self.b) } } }

现在,如果我们尝试将我们的数据移走,我们会遇到编译错误:

pub fn main() { let mut test1 = Test::new("test1"); let mut test1 = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test1) }; Test::init(test1.as_mut()); let mut test2 = Test::new("test2"); let mut test2 = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test2) }; Test::init(test2.as_mut()); println!("a: {}, b: {}", Test::a(test1.as_ref()), Test::b(test1.as_ref())); std::mem::swap(test1.get_mut(), test2.get_mut()); println!("a: {}, b: {}", Test::a(test2.as_ref()), Test::b(test2.as_ref())); } use std::pin::Pin; use std::marker::PhantomPinned; #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, _marker: PhantomPinned, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Self { Test { a: String::from(txt), b: std::ptr::null(), _marker: PhantomPinned, // This makes our type `!Unpin` } } fn init(self: Pin<&mut Self>) { let self_ptr: *const String = &self.a; let this = unsafe { self.get_unchecked_mut() }; this.b = self_ptr; } fn a(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &str { &self.get_ref().a } fn b(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &String { assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first"); unsafe { &*(self.b) } } }

类型系统会阻止我们移动这些数据。

重点记住,固定到栈总是依赖你在写

unsafe代码时提供的保证。例如,我们知道了&'a mut T的 被指向对象(pointee) 在生命周期'a期间固定,我们不知道被&'a mut T指向数据是否在'a结束后仍然不被移动。如果移动了,将会违反固定的协约。另外一个常见错误是忘记遮蔽(shadow)原本的变量,因为你可以释放

Pin然后移动数据到&'a mut T,像下面这样(这违反了固定的协约):fn main() { let mut test1 = Test::new("test1"); let mut test1_pin = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test1) }; Test::init(test1_pin.as_mut()); drop(test1_pin); println!(r#"test1.b points to "test1": {:?}..."#, test1.b); let mut test2 = Test::new("test2"); mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2); println!("... and now it points nowhere: {:?}", test1.b); } use std::pin::Pin; use std::marker::PhantomPinned; use std::mem; #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, _marker: PhantomPinned, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Self { Test { a: String::from(txt), b: std::ptr::null(), // This makes our type `!Unpin` _marker: PhantomPinned, } } fn init<'a>(self: Pin<&'a mut Self>) { let self_ptr: *const String = &self.a; let this = unsafe { self.get_unchecked_mut() }; this.b = self_ptr; } fn a<'a>(self: Pin<&'a Self>) -> &'a str { &self.get_ref().a } fn b<'a>(self: Pin<&'a Self>) -> &'a String { assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first"); unsafe { &*(self.b) } } }

固定到堆上

固定 !Unpin 类型到堆上,能给我们的数据一个稳定的地址,所以我们知道我们指向的数据不会在被固定之后被移动走。和在栈上固定相反,我们知道整个对象的生命周期期间数据都会被固定在一处。

use std::pin::Pin; use std::marker::PhantomPinned; #[derive(Debug)] struct Test { a: String, b: *const String, _marker: PhantomPinned, } impl Test { fn new(txt: &str) -> Pin<Box<Self>> { let t = Test { a: String::from(txt), b: std::ptr::null(), _marker: PhantomPinned, }; let mut boxed = Box::pin(t); let self_ptr: *const String = &boxed.a; unsafe { boxed.as_mut().get_unchecked_mut().b = self_ptr }; boxed } fn a(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &str { &self.get_ref().a } fn b(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &String { unsafe { &*(self.b) } } } pub fn main() { let test1 = Test::new("test1"); let test2 = Test::new("test2"); println!("a: {}, b: {}",test1.as_ref().a(), test1.as_ref().b()); println!("a: {}, b: {}",test2.as_ref().a(), test2.as_ref().b()); }

一些函数需要他们协作的 future 是 Unpin 的。为了让这些函数使用不是 Unpin 的 Future 或 Stream,你首先需要这个值固定,要么用 Box::pin(创建 Pin<Box<T>>)要么使用 pin_utils::pin_mut!(创建 Pin<&mut T>)。Pin<Box<Fut>> 和 Pin<&mut Fut> 都能用作 future,并且都实现了 Unpin。

例如:

use pin_utils::pin_mut; // `pin_utils` is a handy crate available on crates.io

// A function which takes a `Future` that implements `Unpin`.

fn execute_unpin_future(x: impl Future<Output = ()> + Unpin) { /* ... */ }

let fut = async { /* ... */ };

execute_unpin_future(fut); // Error: `fut` does not implement `Unpin` trait

// Pinning with `Box`:

let fut = async { /* ... */ };

let fut = Box::pin(fut);

execute_unpin_future(fut); // OK

// Pinning with `pin_mut!`:

let fut = async { /* ... */ };

pin_mut!(fut);

execute_unpin_future(fut); // OK

总结

-

如果

T: Unpin(默认会实现),那么Pin<'a, T>完全等价于&'a mut T。换言之:Unpin意味着这个类型被移走也没关系,就算已经被固定了,所以Pin对这样的类型毫无影响。 -

如果

T: !Unpin, 获取已经被固定的 T 类型示例的&mut T需要 unsafe。 -

标准库中的大部分类型实现

Unpin,在 Rust 中遇到的多数“平常”的类型也是一样。但是, async/await 生成的Future是个例外。 -

你可以在 nightly 通过特性标记来给类型添加

!Unpin约束,或者在 stable 给你的类型加std::marker::PhatomPinned字段。 -

你可以将数据固定到栈上或堆上

-

固定

!Unpin对象到栈上需要unsafe -

固定

!Unpin对象到堆上不需要unsafe。Box::pin可以快速完成这种固定。 -

对于

T: !Unpin的被固定数据,你必须维护好数据内存不会无效的约定,或者叫 固定时起直到释放。这是 固定协约 中的重要部分。